Federal Reserve officials decided Wednesday to start gradually reducing their massive economic stimulus program.

Beginning in January, the Fed will buy $75 billion in bonds each month, down from the $85 billion it had been buying since September 2012.

"In light of the cumulative progress toward maximum employment and the improvement in the outlook for labor market conditions, the Committee decided to modestly reduce the pace of its asset purchases," the Fed said in a statement.

The Fed decided to cut back on both types of bond purchases -- mortgage-backed securities and Treasuries -- by $5 billion per month each.

The bond-buying program has become so large, it's expected to push the Fed's assets to $4 trillion this week -- money the Fed basically created out of thin air.

The new cut represents the beginning of a gradual wind-down process which Wall Street has nicknamed "tapering."

But the complete end to Fed stimulus is still probably years away.

Fed officials have been stressing lately that tapering does not mean "tightening." In fact, the Fed extended its commitment to keep short-term interest rates "exceptionally low" until either the unemployment rate falls to around 6.5% or the inflation rate exceeds 2.5% a year.

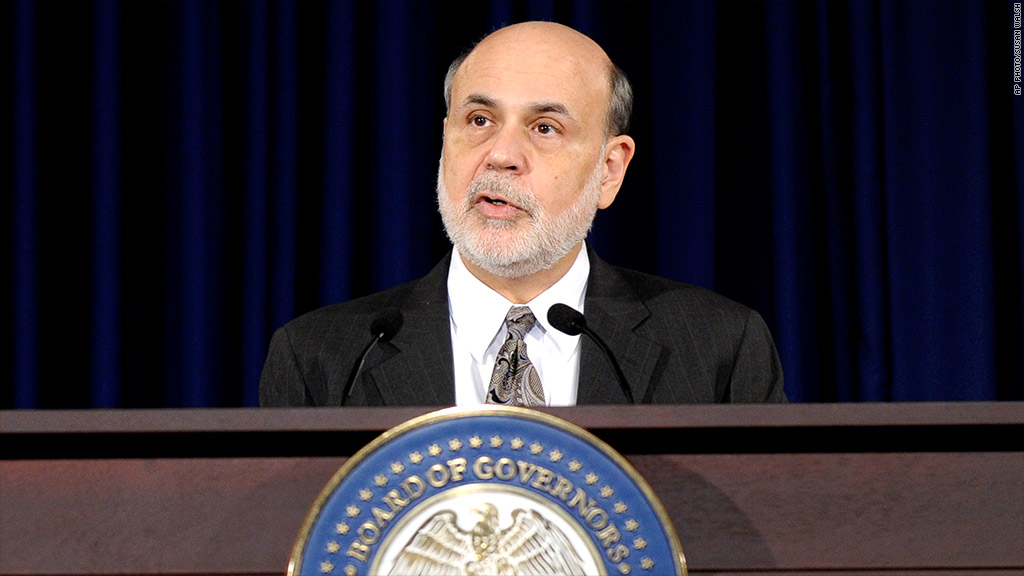

At a press conference immediately following the announcement, Bernanke stressed that the Fed's actions did not amount to a withdrawal of support for the economy. "Nothing we did today was intended to reduce accommodation," he said.

Most officials expect rates to rise in 2015, despite the fact that inflation will likely still be below the target at that point.

Bernanke also explained that the Fed had "enhanced" its forward guidance on keeping interest rates low.

"The committee is determined to avoid inflation that is too low, as well as inflation that is too high," Bernanke said.

But rates will remain low for a while, so consumers can still expect to lock in historically cheap rates on mortgages, car or business loans, albeit probably not at the record lows seen earlier this year.

Stocks jumped following the announcement, with the Dow gaining 200 points after the news.

Related: Will the market actually cheer tapering?

How we got here: Traditionally, the Fed has used low interest rates to stimulate the economy in times of stress, but in the most recent financial crisis, it was forced to take unprecedented measures.

First, the Fed slashed its key interest rate to near-zero in 2008.

Next, in a program known as "quantitative easing," or QE, the Fed started buying bonds like U.S. Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities in an attempt to lower long-term interest rates too.

That second move came in three rounds that have since been nicknamed QE1, QE2 and QE3.

Among them, QE3 was the only program that wasn't given an explicit end-date. Instead, the Fed said it was looking for substantial improvement in the job market. But there's room for interpretation on what exactly that means. The Fed already botched some of its communications surrounding the word "substantial."

Back in May, for example, Chairman Ben Bernanke said he believed the Fed would start to taper "later this year," ending the bond-buying program completely in 2014, when the unemployment rate falls to around 7%.

Wall Street believed him, and stocks started falling and bond yields started rising over the summer.

But then the Fed met in July, September and October without taking action, and the unemployment rate fell to 7% in November, but still there was no taper.

Only one Fed member -- Eric Rosengren of the Boston Federal Reserve -- formally dissented against Wednesday's decision. He felt that unemployment was still too high and inflation was still too low to begin pulling back on stimulus.

Bernanke will attend one more policy meeting next month, before his term as Fed chair ends January 31. The rest of the Fed's exit strategy will have to be left to his presumed successor, Janet Yellen.

President Obama nominated Yellen for the position in October, and the Senate is expected to confirm her this week.